Archive for the ‘mothers and daughters’ Tag

My mother died last week. In going through some of her papers I found letters I’d written her that she’d saved, along with some cards I made. Among the letters, one, in particular stood out, written when I was 25, which was a long time ago.

While reading it, I was struck by how much of the content had not changed. It was a thank you note, but not for anything materialistic. Rather, I thanked her for the wonderful qualities, ones she, wittingly or not, passed onto me. These included, but definitely weren’t limited to, instilling in me the importance of a sense of humor, independence, sensitivity, and the certainty of her love for me.

(In looking at the Halloween card I made, I realize she also imparted an appreciation for mysteries.)

My mom was also my closest friend. The only time I recall that not being the case was when I was 13. That age explains it all. Otherwise, we laughed a lot, shared details of our lives once I moved away from home as a young adult and ever since. We spoke by phone almost daily – until about six weeks before she died. Talking on the phone was difficult for her, so the conversations practically ceased. I think that’s when the grieving process started for me.

I was with her when she died. I’m glad that card wasn’t the only time I expressed my appreciation for all she gave me. I’m saddened I can’t keep letting her know.

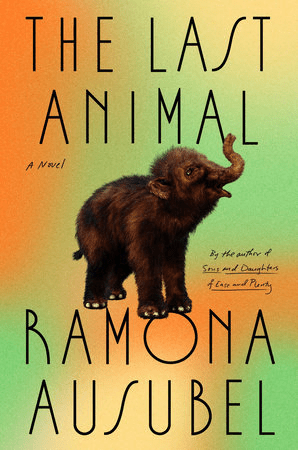

The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel could easily be titled The Last Family because it’s about a mother and her teenage daughters trying to keep it together.

Jane is a paleo biologist, whose husband died in a car accident a year ago. Eve and Vera are 15 and 13, but wiser than most kids their age. This is, in part, due to their strong bond with each other and to tagging along with their parents on scientific expeditions around the world.

The novel is rich with humor and pathos as the trio treks to Siberia, Iceland and a private animal refuge in Northern Italy. As Jane becomes increasingly disappointed in her ability to be heard/seen as a legitimate scientist, the girls assume responsibility for her care. Grief fills all three as they move forward with their lives while making scientific and personal discoveries.

Part of which involves Jane’s theft of genetically-created embryos of a woolly mammoth, which are clandestinely inseminated into an elephant at the Italian refuge.

What ensue are questions of ethics, sexism and a family struggling for some semblance of normalcy. The latter is particularly difficult given the possibility of introducing an extinct prehistoric animal to the modern world.

Eve and Vera are remarkable characters even if, at times, difficult to consider realistic because they’re wise beyond their years, self-aware teens. They have enough sense to be skeptical of what the future holds, yet are naïve enough to hope for the best – attitudes worth emulating at any age.

The Last Animal

Four Bookmarks

Riverhead Books, 2023

278 pages

Except for lives lost and residual health issues faced by those infected by COVID-19, the pandemic was, in many ways, positive. It was a time for introspection and, if lucky, being together. This is the starting point for Tom Lake, Ann Patchett’s newest novel.

It’s cherry picking season on the Nelson family orchard in northern Michigan. Due to the pandemic, Lara and Joe Nelson’s young adult daughters are home to help harvest the crop. They plead with their mother to tell the story of her long-ago romance with Duke, a famous actor.

The narrative seamlessly moves between Lara’s descriptions of present-day life and her involvement with Duke. They met doing a summer stock production of Our Town. Duke was beginning his trajectory while Lara awaited release of a movie she was in. However, it, and her role as Emily, was as far as her acting career would go.

Lara does little to embellish the relationship and spares few details regarding the intensity of their short-lived affair; she, via Patchett, tells a good story over the span of several days. She’s happily married to Joe, relishes her life on the farm and being with her daughters. How this evolved is entangled in Duke’s story, which has several (credible) surprises. Fortunately, readers are privy to info Lara does not share with her kids.

Patchett’s writing is engaging from page one and never wavers. Like those in Thornton Wilder’s play, Patchett has created a family of extraordinary characters living conventional lives in unusual times.

Tom Lake

Five Bookmarks

Harper, 2023

309 pages

Of Women and Salt by Gabriela Garcia is a novel I wanted to fall in love with. Unfortunately, despite it having so many elements I’m drawn to, that didn’t happen.

With the exception of a Mexican immigrant and her young daughter, Garcia’s debut work focuses on the women in a Cuban family, several generations removed. Immigration, abuse, mother/daughter relationships, addiction, miscommunication and loss are brought together through glimpses into each woman’s life. The result is a disjointed narrative.

Loss is the most dominant thread, beginning with Maria Isabel in a cigar-rolling company in rural Cuba in 1866. As the only female roller, hers was the most compelling story. To keep the workers engage, a man read either from a novel or newspaper until war made it impossible to continue.

The next chapter is a leap to Miami 2014, where Jeanette, Maria Isabel’s great-great granddaughter is a grown woman and substance abuser. She’s a much less engaging character; yes she makes poor choices, but more is needed than illustrations of her bad decisions. Although she briefly helps the young daughter of the Mexican neighbor who’s apprehended by ICE, there’s little else appealing about her.

The characters need to be fully developed. It’s as if they’re faded photos without any nuance. While this is a work of fiction, the experiences the women endure are important because, unfortunately, they’re not unique. The impact would be greater if, instead of multiple situations, more details were limited to only a few.

Of Women and Salt

Two-and-a-half bookmarks

Flatiron Books, 2021

207 pages

As disturbing as The Push is by Ashley Audrain, it’s nearly impossible to put down. It’s not exactly like watching a disaster unfold before your eyes, but it’s close.

Blythe Connor’s mother was not an exemplary maternal role model; although they never met, neither was Blythe’s grandmother. Audrain offers some background about these women, which helps explains the younger woman’s anxiety about becoming a mother herself. The pressure is magnified by her husband, Fox, who’s certain she’ll be a Mother of the Year candidate.

After their daughter, Violet, is born, Fox is the parent of choice; Mother and daughter never bond. Initially, Blythe is certain it’s her fault; however, as Violet gets older, Blythe becomes convinced she’s not entirely to blame. Something isn’t right with Violet, and Fox refuses to acknowledge it.

Blythe and Fox’s marriage falls apart, something revealed early in the novel. Audrain uses a direct address approach to Fox for Blythe to explain her side of the story. She recounts falling in love with him in college, the early days of their marriage, and Violet’s birth which marks the beginning of problems. She tries to rationalize the issues with Violet are only in her imagination. When the couple has a second child, Blythe is surprised by her deep feelings for him.

Audrain has crafted a profound, often dark, family portrait. Blythe is a sympathetic character, but the haunting question is whether or not she’s a reliable narrator. The result is compelling.

The Push

Four-and-a-half Bookmarks

Pamela Dorman Books, 2021

307 pages

In Lily King’s Writers & Lovers 31-year-old Casey Peabody has been working on a novel for six years. Her mother recently died, she’s in debt and she works as server. She’s ended one relationship and soon becomes involved with two other men.

There’s no smut here. Instead, King creates intrigue and empathy for Casey, who’s kind, good with dogs and kids, and lives on the fringe of Boston’s literary society. She has writer friends, becomes involved with Oscar, an established author, and Silas, a struggling writer, all while agonizing over her own work. King’s characters are warm, likable people.

If this were a play, Casey would be upstaged by Oscar’s two young sons. He’s published, widowed and is several years older than Casey. She deliberately shares little of her writing efforts with him, but his boys are awfully cute. Then there’s Silas who’s closer to her age, teaches and writes in his spare time. Silas is initially off-putting because shortly after meeting Casey and making arrangements for a date, he leaves town for an indeterminate time. Not a great way to make a good impression; although he does return, which when things get complicated.

Casey’s deceased mother is an important character. She’s who Casey would turn to about her life’s dilemmas. Instead, Casey’s left alone to figure out things for herself. The result is a back-and-forth sideline cheering for one man than the other, all while rooting for Casey to not only finish her novel, but publish it.

Writers & Lovers

Four+ Bookmarks

Grove Press, 2020

324 pages

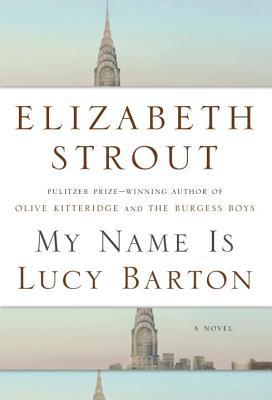

My Name is Lucy Barton is a statement and not only the title of Elizabeth Strout’s new novel. It’s an affirmation as Lucy reflects on the relationship with her mother, which is like a faulty wire: occasionally there’s no connection.

Lucy is from a rural Illinois town where growing up her family lived so far below the poverty line as to make it seem something to attain. Lucy’s life is revealed as she lies in a hospital bed with a view of the Chrysler Building in New York City talking with her mother whom she hasn’t seen or spoken with in years. Strout is methodical as she merges Lucy’s past with the present.

The rich, stark pacing and imagery serve to expose family dynamics in the narrative. That is, Strout’s writing provides enough detail to shape a situation or character, but not so much that there is little left to the imagination. In fact, this is what makes some aspects harrowing: imagining what life was like for young Lucy. She lived with her older siblings and parents in a garage until age 11.

Her mother’s brief presence provides the vehicle to see Lucy’s past; the extended hospitalization gives Lucy time to consider her adult life as a mother, wife and writer.

Lucy should despise her parents and her past, yet she doesn’t. Her family was shunned and her parents were apparently abusive in their neglect. Lucy is grateful for her mother’s presence. The mother-daughter bond, at least from Lucy’s perspective, overrides past sins.

My Name is Lucy Barton

Four and a half Bookmarks

Random House, 2016

191 pages

Where’d You Go, Bernadette by Maria Semple is engaging, funny, poignant, and even a bit silly. Set primarily in Seattle, the story also includes a few situations in Los Angeles and the Antarctic as Bernadette Fox tries to ward off a nervous breakdown in an environment seemingly designed to push her over the edge.

Bernadette is a semi-misanthrope; she dislikes nearly everyone except her husband, Elgie, and their daughter, Bee. Bernadette doesn’t make it easy to like her. She refuses to get involved with the parent groups at Bee’s school, and she avoids interaction – no matter how casual – with others to such an extreme that she relies on a virtual personal assistant who lives in India.

Semple has created an appealing dysfunctional family that has trouble meshing with an often-dysfunctional world. Bernadette, a one-time architect, is, in fact, a genius; she’s a past recipient of a McArthur Foundation Genius Grant. But she responds to stressful situations through radical reactions, including disappearing. Bernadette’s story is told through emails, letters and mostly Bee’s eyes. Bee is no intellectual slouch herself. She’s convinced there’s a logical explanation for her mother’s absence. And here’s where the real adventure begins as Bee sets off to find Bernadette.

Russian spies, potential identity thieves, private school students, and parents blind to their children’s excesses and foibles are just a few of the extras populating Semple’s novel. There are plenty of laugh-out-loud situations as well as a few shoulder-shrugging moments as Bee, who has a very good understanding of her mother, refuses to stop looking.

Where’d You Go, Bernadette

Four-and-a-half Bookmarks

Little, Brown and Co., 2012

326 pages

Often, stories within stories are enchanting, muddled, lopsided or boring. Fortunately, Winter Garden by Kristin Hannah is captivating without any confusion. One narrative is not more interesting than the other; both have equal appeal.

Much of what makes Hannah’s novel so successful is the clever way in which her characters evolve. Sisters Meredith and Nina are grown women who have always basked in the light of their father’s love. Meredith is the older sister, pragmatic and harried; Nina lives the adventurous life of a freelance photographer. Theirs is not a close a relationship. If not for Evan, their father, there would be little for anyone in the family to hold dear.

Unlike Evan, their mother is a cold, distant woman incapable of showing or articulating affection. This could be a black and white story, but Hannah has enough sense, and talent, to show the nuances. A secret past, painful memories and the harsh reality of war culminate in a fairy tale the sisters’ mother is ultimately compelled to tell. The story moves from the idyllic, contemporary life on the family’s apple orchard to cold, war-torn Russia. Like any good fairy tale, this one begins with a handsome prince, an evil overseer, and a young girl who falls in love.

As the fairy tale evolves, it’s clear this the only way the mother can explain herself and for her daughters to recognize their own strengths, weaknesses and connections. There’s nothing jumbled in either side of Hannah’s engaging account.

Winter Garden

Four Bookmarks

St. Martin’s Griffin, 2010

391 pages

Shilpi Somaya Gowda’s first novel, Secret Daughter, is about families – especially mother-daughter relationships. Two women, one unable to have a child and the other unable to keep hers, are the primary focus – along with Asha, the daughter given up by one and adopted by the other.

Somer, a pediatrician in the San Francisco Bay area is married to Kris, a surgeon originally from Mumbai. Across the world in an Indian village, Kavita gives birth to a daughter she knows her husband does not want, and will not let her keep. Although the women never meet their lives are unwittingly bound when Kavita leaves her child at an orphanage. Through a series of coincidences that often only occur in fiction, the girl, Asha, is adopted by Somer and Kris.

Gowda’s narrative moves from the Bay Area to Mumbai, as it shifts from one woman’s perspective to the other, before, thankfully, settling on Asha. Somer‘s character is whiney and distant; Kavita is mostly sad and compliant. Despite environment and genetics working against her, Asha grows up to be an intelligent, inquisitive young woman. That’s not to say, she is flawless. At her worse, as a teenager, she is rude and insensitive; at her best, as a college student interning at a Mumbai newspaper, she is empathetic and appreciative. Of course, it takes time for the latter qualities to evolve.

Gowda’s writing is strongest describing the contrasts between India’s wealthy and the destitute. The colors, sights, and smells are vivid – even when the reader might prefer otherwise.

Secret Daughter

Three Bookmarks

William Morrow, 2010

339 pages